Photos compliments of the International Family Nursing Association: https://internationalfamilynursing.org/2015/04/12/family-nursing-in-action-request-for-photos/

Photos compliments of the International Family Nursing Association: https://internationalfamilynursing.org/2015/04/12/family-nursing-in-action-request-for-photos/

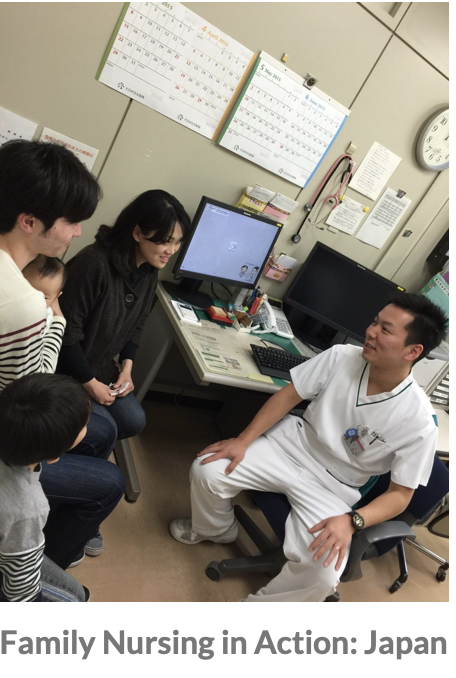

I was invited to offer a keynote at the British Columbia Quality and Safety Council‘s preconference forum on Patient and Family Centered Care. Yesterday’s group wasn’t my usual tribe of family nursing scholars and practitioners. Instead it was an interesting group of health care providers, legislators, administrators, and patient care advocates who care about “Quality and Safety” and who have varied and diverse ideas about what “patient and family centered care” is and how to do it. For many, patient and family centered care is about creating systems and policies to reduce waste and “shadowing” to understand what patients and families actually experience in a health care setting. It may mean changing the policy about “visiting hours” or conducting “bedside rounds” in hospitals. The solutions are focused on reducing redundancy and long waiting hours and insuring patients are kept informed–all very useful ways to insure that patients and their families receive good, “safe” care and are considered “partners” in care. My keynote address offered a bold assertion that at the heart of patient and family care are particular kinds relationships between patients, families, and health care providers that are shaped, in large measure, by the beliefs of the health care provider. A belief that I have more expertise so I am right which makes me blind to your preferences, a belief that I have no time to involve families, or a belief that if I talk to families and patients about things that matter to them, I might “open a can of worms”. These beliefs can constrain if and how relationships are established and maintained with patients and families.

Through the development of our “Calgary Practice Models” including the Calgary Family Assessment and Intervention Models, the Illness Beliefs Model, and the Trinity Model we have developed a number of interventions that address patient’s and families’ illness concerns and explore how illness has impacted their lives and relationships. A format for offering a brief therapeutic conversation has been proposed by my colleagues Lorraine Wright and Maureen Leahey called the “15 minute (or shorter) family interview” (see Family Nursing Resources for more information about books and DVD’s). A number of useful questions include “How can we be most helpful to you and your family during your hospitalization?” or “If you could have just one question answered in our time together, what would that question be?” or “Who in your family is suffering the most?“. We advocate asking these questions to both patients and family members together based on a belief that illness is a family affair! The patient is only half of the patient, the other half is the family. These practice skills that we call Family Systems Nursing are easy to learn but unfortunately they are not being used routinely in health care settings. Research findings from my colleagues around the world indicate that a brief therapeutic conversation makes a big difference to patient and family satisfaction scores and to the work quality and satisfaction scores of the nurse. It seems that there are still very few health care providers on the front line who know about this way of talking with patients and families or who see the value of these kind of conversations in a health care system that is overburdened and chaotic.

What is even more fascinating to me is that very few advocates of “patient and family centered care” seem to see the link between the value of therapeutic conversations with patients and families and the quality and safety metrics in health care. My hypothesis is that if patients and family members felt like they mattered and were welcomed, included, and their illness suffering was acknowledged by health care providers, there would be fewer errors made by health care providers and greater satisfaction with care would be reported by families. We need to gather more data about how therapeutic conversations influence these variables. They say that the diffusion of innovation takes 17 years. Nurses have been building this knowledge about how to care for families the past 30 years. I can hardly wait for a tipping point in health care to occur where therapeutic conversations would be usual practice offered to ALL patients and families in our care.

It is clearer to me than ever that all of this “buzz” about Patient and Family Centered Care in this geographic region is exciting but the skills training and coaching and mentoring to improve health care provider beliefs and behaviors with families is still not well understood or considered important in the larger systems plans to “change the culture of health care”. Information, respect, and partnering with patients and families is critically important. What is still missing is ability to identify and acknowledge illness suffering with patients and families through a therapeutic conversation that is offered with compassion. There is still a lot of work to be done to convince those who are leading cultural transformation to address the “heart of the matter” which are beliefs and relational skills for therapeutic conversation that every health care provider could bring to every encounter with every patient and family. Talking, I believe, can be healing (and life-saving)!